Formula 1 may be the arena where speed and competition take the spotlight, but the work that makes it all possible unfolds far from the track. It is the invisible side of a championship which grows more complex with every passing year, evolving into a vast ecosystem that stretches well beyond the performance of a single car. A hidden dimension that deserves a closer look, because only by doing so the scale of the effort behind it can be fully appreciated.

And it is there, in that backstage world of numbers, data, and images, that one of the FIA’s most sophisticated tools comes to life: RaceWatch, the ‘digital brain’ developed by the governing body in partnership with Catapult. Without it, coordinating, managing, verifying, and interpreting every event in real time during a grand prix would be significantly more challenging.

Meeting the demands of an increasingly complex F1 requires advanced tools, and looking at how this platform works also means understanding the FIA’s commitment to improving safety and sporting fairness.

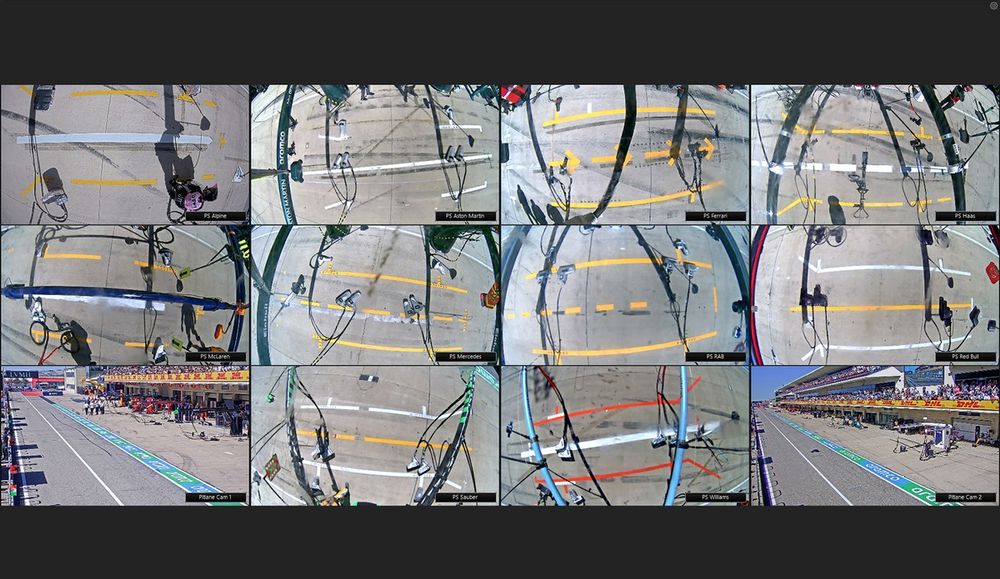

Around 200 video and audio feeds to manage

Chris Bentley, the FIA’s single-seater head of information systems strategy, told Autosport: “We have been working with RaceWatch for 15 years. A lot of people don’t realise the amount of time that we’ve been working on these systems all the way back when it was just part of a video review system. But we’ve been able to expand the capabilities of this platform to be more what we call a competition management platform.

“This system goes far deeper into many of the functions we oversee: from race operations, such as incident detection and track‑limits monitoring, to the technical department led by Joe Bauer, PU monitoring, tyre management and including the operation of the scales you see in qualifying when cars stop at the start of the pitlane. All of these elements are integrated into RaceWatch.”

It is a platform in constant evolution, adding new features weekend after weekend. Just last year, the FIA and Catapult updated the system with 23 major and many other minor releases, improving not only its functionality and data visualisation but also the governing body’s ability to handle an ever‑growing volume of information. On average, around 200 audio and video signals are monitored during every grand prix.

A portion of the video feeds, which also includes the track’s closed-circuit cameras, with which the FIA monitors the session

Photo by: FIA

This platform relies not only on the cameras from the FOM‑managed broadcast feed, but also on the closed‑circuit CCTV network around the track, the cameras integrated into the starting‑grid panels, the pitlane cameras above the pitstop area to ensure that every penalty is served correctly, parc ferme cameras above each car in the garages and every driver’s onboard stream. On the audio side, in addition to the intercom, the system can also manage, detect and transcribe audio sources, such as team radio.

One of the innovations introduced for 2025 involves the cameras integrated into the starting grid panels. The system can recognise a car’s behaviour in real time and therefore not only alert Race Control in the event of a potential false start, but also warn drivers if a car has stalled on the grid, further improving safety.

Until 2024, the regulations allowed stewards to issue a penalty only if the sensor detected movement. However, there were cases where drivers moved without the sensor registering any anomaly and therefore could not be penalised, as happened with Lando Norris in Saudi Arabia 2024. The investment in cameras positioned on the starting grid now makes it possible to assess these situations without relying only on the sensor.

The system can automatically detect incidents

Through AI, RaceWatch can also track every car on the circuit in real time and analyse its behaviour. This capability has a direct impact on safety: by combining all camera feeds with the complex positioning system developed by the FIA and Catapult, officials can understand what is happening on track in real time.

By cross‑referencing all incoming data, the system learns the “ideal” racing line and can automatically flag potential incidents or off‑track excursions. When it detects an anomaly, it highlights the area in yellow on the video feed and sends an alert to Race Control, which can then intervene as needed.

“We have models of what we expect the car to do,” said Gareth Griffith, CTO of Catapult. “We have a reference lap and if there’s any kind of anomaly, let’s say a car is going much slower than it should be at a certain point, or if two cars are moving very slowly together, we know there’s likely been an incident. At that point the system flags it, and you can go straight to the relevant camera.”

Pitlane cameras to monitor whether a penalty is being served correctly during pitstops

Photo by: FIA

Not just cameras and audio: more than 300 sensors feed the system

All of this video infrastructure is integrated with the vast amount of data coming from the sensors installed on the cars, including those used for the telemetry. With such a large flow of information, the challenge lies not only in processing it, but also in understanding what is needed and how to visualise that data. This is where RaceWatch truly makes a difference for the FIA: the platform keeps all this data synchronised and immediately accessible.

This allows officials to assess how a car behaves relative to the reference model while also giving them all the tools needed to verify a potential infringement.

Bentley said: “For example, we have data on driver input, such as brake, steering angle and throttle, because when you analyse an incident you need to understand what the driver is doing, or whether they lift under a yellow flag.

“We also have information on the tyres, their pressures, and how they are heated in the garages. We have technology that connects to the teams’ TPM systems and shows what is being heated and at what temperatures. So, if there is any alert, our technical guys can see how tyres have been heated and what the teams are doing with the heating process. Also, when the teams have to return the tyres [after a session], it’s all done electronically.”

For every incident, a synchronised mosaic and archive are created

If the stewards decide an episode requires investigation, the system can generate a mosaic‑style view, synchronising video from multiple cameras with telemetry data. This allows them to analyse a potential infringement from several angles, while also having a clear view of the driver’s actions.

The stewards can not only rely on CCTV cameras but also on the international feed, the drivers’ onboard footage, also from the cars around, ensuring they have as many reference points as possible. Once they determine how to proceed, the stewards relay their decision to Race Control, which then communicates it to the teams and the public.

RaceWatch is able to recognise and report any accidents

Photo by: FIA

This is one of the most advanced tools available to the stewards, as it allows them to analyse an incident within minutes using multiple synchronised angles paired with the relevant telemetry data. Crucially, once a decision is made, all the videos and data used are stored online in the Catapult FIA Hub and can be accessed at any time, allowing officials to review similar cases when needed.

One of the FIA’s goals is to ensure transparency and consistency, applying similar criteria to incidents that fall under the same type of infringement. Not an easy task, which is precisely why the archive plays such a fundamental role: within seconds, the stewards can check how comparable cases were assessed in the past, consulting not only the final document but also all associated video and telemetry data. In the interest of transparency, this archive is also accessible to the teams.

This is where track limits control is born

RaceWatch plays an increasingly central role for the FIA: with AI several processes are now automated, making session management easier and reducing the pressure on Race Control and the stewards. A significant example is the automation of blue flags: it might look like a tiny tweak, yet it has made the procedure noticeably faster and more efficient.

It is estimated that, in the past, an operator could end up displaying more than 150 blue flags in a single race. Automating this process has therefore enabled the FIA to streamline and speed up the review phase. The same principle applies to track limits: thanks to computer vision, the system can recognise the car and determine whether it has crossed a specific reference point.

Once the system identifies the area where a car is expected to end up, it recognises the shape of the single‑seater and, using a series of reference markers, including the blue line introduced in 2024 specifically for this purpose, it can determine whether a driver has exceeded track limits, automatically flagging the episode to the relevant stewards.

Before the introduction of AI, the FIA relied on a small team, including staff positioned at key corners to monitor for infringements in person. Naturally, this process required time. With the introduction of the AI‑based system, approximately 95% of cases are now processed automatically, leaving only 5% for manual review by the stewards.

Using computer vision, RaceWatch is able to recognise and report any track limits

Photo by: FIA

This reduces the FIA’s workload and speeds up operations, providing teams with feedback within seconds. One of the innovations planned for 2026 moves precisely in the direction of maximum transparency: the governing body will be able to send teams the images used to determine a track‑limits infringement, giving them the exact reference at the moment the decision is communicated.

Responding to problems to improve the system

Of course, no system can ever be considered infallible: unexpected situations are inevitable and will always arise, which is why the FIA continues to introduce improvements, turning every issue into an opportunity to understand what isn’t working and improve what already exists.

One example is what happened at the 2023 Saudi Arabian Grand Prix. Lance Stroll’s car stopped off‑track, in an area not covered by cameras, and the car’s GPS signal was turned off. With no clear visual on the Aston Martin, the FIA was forced to deploy the Safety Car to recover it, even though it was actually in a safe location.

Since then, a new system has been introduced that estimates the car’s position and automatically selects the relevant camera angles, while also displaying the onboard footage of any cars passing through that zone.

Griffith explained: “From that incident, we developed this new system whereby, whenever a car stops, we immediately get a view of the corner where the last GPS signal was detected. We know all the cameras and their angles, so the relevant ones are selected automatically.”

Another significant example is the introduction of the Virtual Safety Car, developed in just a few weeks to be integrated into RaceWatch and improve safety. It’s a case that illustrates the FIA’s approach: learning, adapting, and innovating. Much of this work unfolds behind the scenes, yet it supports every session, every decision, and every moment of an increasingly complex F1.

We want to hear from you!

Let us know what you would like to see from us in the future.

Take our survey

– The Autosport.com Team

Read the full article here