It’s amazing to think that the drag reduction system has been a part of Formula 1 for 15 seasons.

Developed as a way to mitigate the chances of processional races, it’s become a part of the furniture – but in the eyes of many, only akin to a mismatched chair stuck in the corner of the living room. “We really must get rid of it,” you muse and yet, 14 years later, it’s still in the corner.

It’ll be gone next year, as the active aerodynamics packages will render it obsolete – but that’s been done out of necessity to limit drag on the straights, reducing the chance of a driver exhausting a battery’s worth of energy in the early stages of a lap. A manual override mode, where the enforced ramp-down in energy deployment at high speeds can be delayed if within one second of the car in front.

Often maligned and viewed by purists as a sticking plaster, the DRS effect has had to be tuned through the years to ensure its efficacy without being too obvious.

Yet, it’s become a necessary evil. When the current regulations were being devised, the plan was to create a formula that dispensed with the need for it entirely. While the reduced wake characteristics of the cars helped drivers to follow more closely in the corners, it cut away much of the slipstream effect on the straights; thus, DRS was retained for 2022 and beyond.

It’s always been true, and a function of simple aerodynamic theory, that DRS is less effective with lower-drag aero packages. DRS works by a) reducing the frontal area of the car, and b) decoupling the two rear wing elements. With less frontal area, the car experiences less air resistance. The power needed to overcome that drag is hence lessened, allowing the car to deploy that power into greater top speed.

Nico Hulkenberg, Sauber, Lance Stroll, Aston Martin Racing

Photo by: Clive Rose / Getty Images

But 2025’s low-downforce packages, seen at Monza and Baku, have been characterised by wing elements with lower angles-of-attack and shallower camber to garner more straightline speed. The current floors generate sufficient downforce in the corners now to offer the balance between lower levels of drag and the tractive force needed to break out of the corners quickly.

The efficiency gains with the low-drag wings, according to Mercedes’ trackside engineering director Andrew Shovlin, has perhaps contributed to the processional nature of this year’s Monza and Baku races.

“With these regs, because so much performance comes from the floor, it’s been driving down the size of rear wings,” Shovlin confirmed. “So now you’re getting to a stage where what would have previously been called the Monaco wing barely appears at any circuits now.

“It used to be the case that was what you were running in Budapest and you’d be running it in Mexico. So generally, people are putting smaller wings on, they create less disturbance so the tow effects are smaller, and then also with a smaller wing you’ve got less DRS effect.

“That’s one of the things in Monza – there’s barely any DRS effect because the wing is so efficient in its high-downforce state that there’s very little drag to get rid of.”

It does somewhat demonstrate the difficulty in attaining a balance with any ruleset. F1’s technical figureheads often want to invoke a certain change, but there will always be a consequence to those modifications – and often, not a particularly desirable consequence.

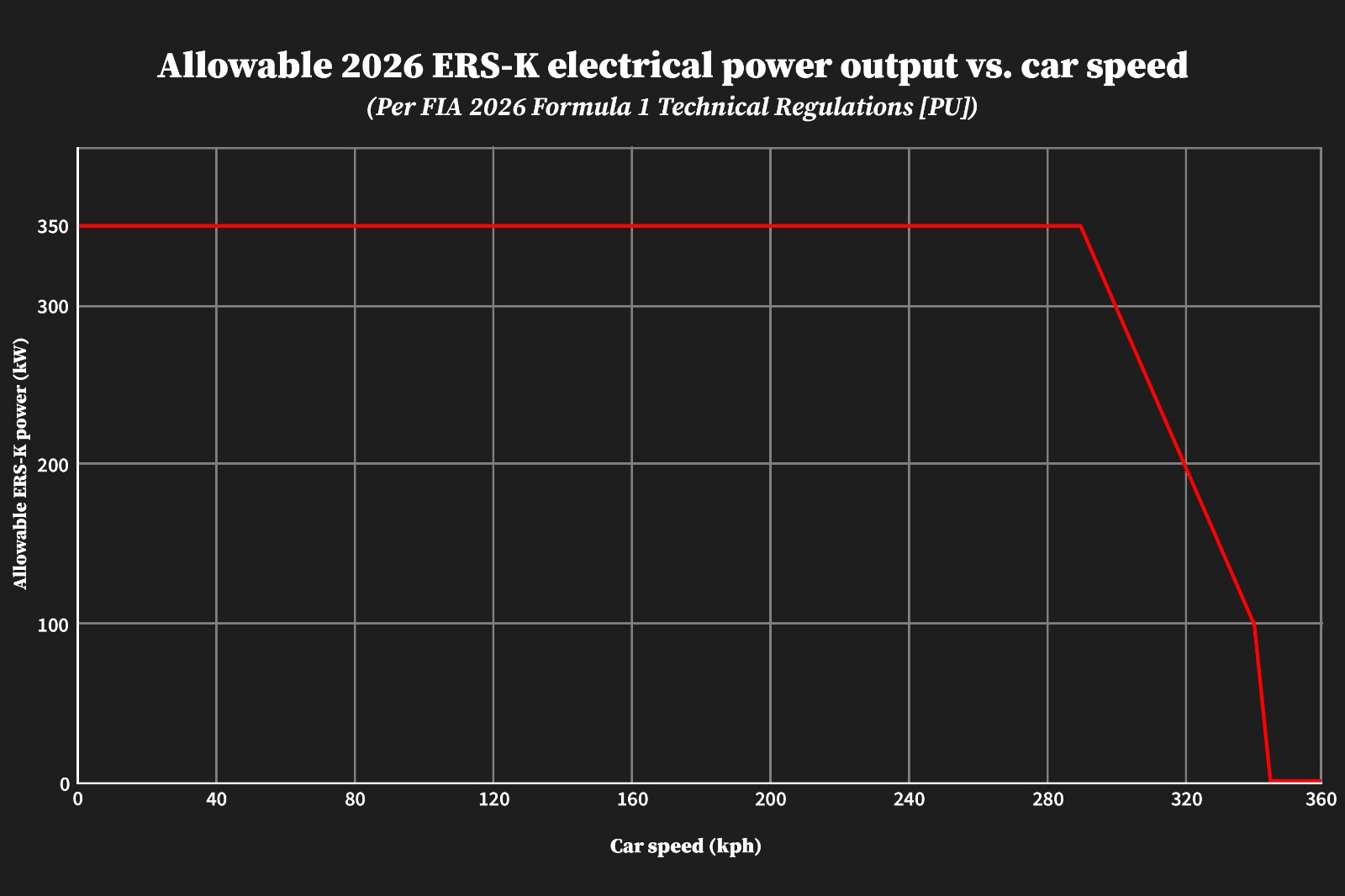

Next year’s override mode will be of interest. Beyond 290kph (180mph) the MGU-K will start to decrease its output from 350kW at a rate where, on reaching 345kph (214mph), it will be at zero – as demonstrated by the graph below.

Photo by: Jake Boxall-Legge

The manual override mode keeps that output at 350kW up until 337kph (209mph), so in essence will allow a chasing driver an electrical power ‘push to pass’ mode for a given window.

It’s not easy to determine, without having seen it in action, what the effect will be and whether it’ll be an adequate overtaking tool. Without being able to develop the power offset, it appears as though it’ll be less effective at lower-speed circuits.

For circuits with long straights, it’ll be a more consistent offset than DRS with a low-drag wing, but it might require careful management depending on how efficient a car is with its energy harvesting tools.

If a manufacturer is struggling to map its power units to pack enough energy back into the battery, then the override might be a luxury it can ill-afford.

And will the viewing public have the same qualms about an override mode as it does about DRS? Or will it be viewed as a symptom of a regulatory set that, so far has proven unpopular? Answers on a postcard, please.

Read the full article here