Regular readers of this column will have noticed – indeed they could scarcely have not noticed! – that over the years Gilles Villeneuve has figured in it a great deal more than any other personality in racing. I make no excuse for this, but would like to try to explain why it was inevitable.

From the start it was apparent to me, and to many others, that Gilles had star quality. I can remember watching him hurl that McLaren M23 round Silverstone during testing in 1977. Times without number he spun the thing, sorted himself out, found first gear and tore away again.

At first sight there seemed to be a desperation about his driving, and I found it somewhat chilling. But two things about it were impressive: he never hit anything, and while he was on the road he was mighty quick. The spins were not the result of being out of his depth.

“Jesus, I spun so many times in the M23,” he would giggle, looking back on it. “But you have to remember the position I was in. All I could think of was getting out of [Formula] Atlantic, making it to Europe, getting into Formula 1. This looked to me like my only chance.

“I was supposed to have four races for McLaren in 1977, but in the end it was only one. I had to learn about the car and track very quickly – I needed to impress everyone in that race. For me, the quickest way to learn the limits of the M23 was to go quicker and quicker through a corner until it spun… Then I knew how quick was too quick!”

Of course, he did impress at Silverstone, in both practice and race. A McLaren contract for 1978 looked a foregone conclusion, but Teddy Mayer made one of his most unfathomable decisions, opting instead for Patrick Tambay.

Thus it was that the legend of Villeneuve and Ferrari began. Association with Maranello gives any driver a certain mystique, but Gilles belonged there, right from the start. Through 1978 he continued his policy of finding the limit by exceeding it, and there were many accidents. But his mechanics shrugged their shoulders, grinned and set about rebuilding. By now they loved the little man, for they knew how much he was giving of himself.

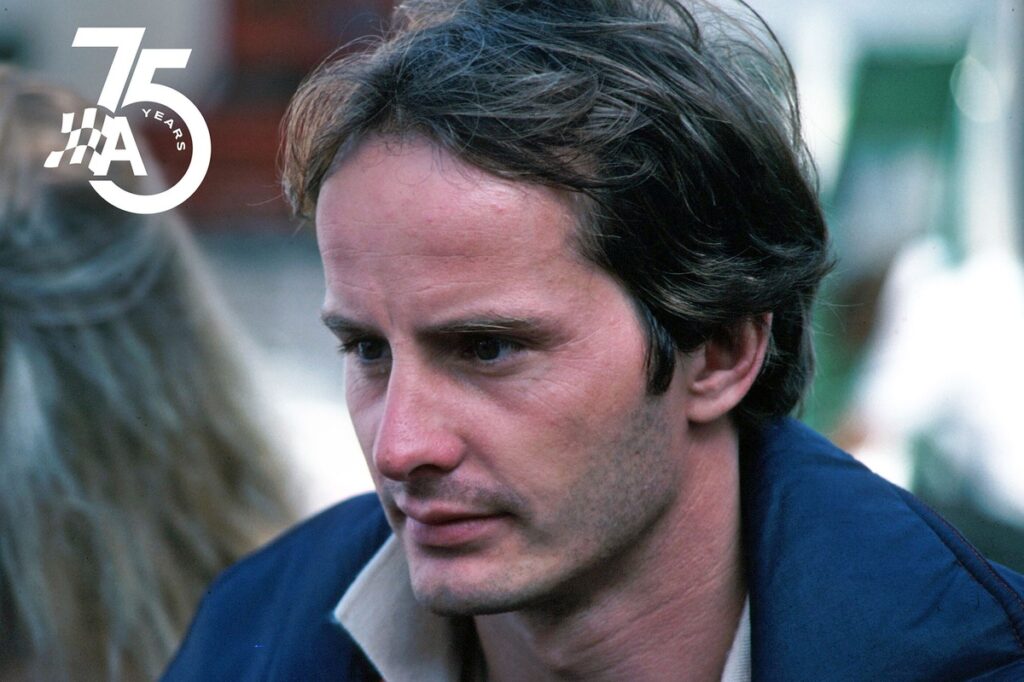

It was, ironically, at Zolder that year that I first got to know him. Here, I felt, was someone central to the sport’s coming years, and I wanted to interview him before he became spoiled. In fact, of course, he never did.

Overlooked at McLaren, Villeneuve was instantly at home at Ferrari in 1978

Photo by: Ercole Colombo

We sat for a couple of hours in the Ferrari transporter, and I found much of what he had to say pretty startling. He had recently walked away from a big shunt in the tunnel at Monte Carlo, and I had been amazed by his coolness immediately afterwards.

“I don’t have any fear of a crash,” was his dispassionate comment. “I never think I can hurt myself. It seems impossible to me.” Come on now, I said, you can’t mean that. “I do!” he replied. “If you believe it can happen to you, how can you possibly do the job properly?

“If you’re never over eight-tenths or whatever, because you’re thinking about a shunt, you’re not going as quick as you can. Most of the guys in Formula 1… well, to me, they’re not racing drivers. They’re doing half a job, and I can’t figure why they do it at all…”

Gilles was always sure his attitude to danger had its roots in his snowmobile days: “We raced those things at 100mph, and quite often got thrown off onto the ice. That gives you a strong heart, you know.”

The stability of Gilles’s family life was tremendously important to him. He liked his kids with him, and Joanne’s presence relaxed him. She did not go to Belgium, of course, which was a mercy

Snowmobiling also gave him the money to start racing cars. He was not one of your rich kids, and money – of which he later earned a great deal – never changed him. That was something else I liked about him, that and his quiet insistence on living by his own rules.

There was the camper, for instance. Gilles hated ritzy hotels for several reasons. First, he slept better in his own bed; second, he preferred hamburgers and steaks and milkshakes to haute cuisine; third, he hated sitting in traffic every morning and evening; fourth, he liked to stay close to the cars, be near what was going on, which of course guaranteed him the adoration of his mechanics; and fifth, if truth be told, he really didn’t care for a lot of people in grand prix racing, and preferred to be where they were not.

“Hey! Shoes!” People unfamiliar with the Villeneuve camper were soon acquainted with the house rules. You slipped your shoes off and left them by the door.

Roebuck felt money and fame never changed Villeneuve during his career

Photo by: David Phipps

“Well,” he would say, “we live here. I don’t want people dragging mud everywhere over the carpet. And anyway,” we would add, with that famous grin, “people feel uncomfortable standing there with no shoes – so they don’t stay long!”

The stability of Gilles’s family life was tremendously important to him. He liked his kids with him, and Joanne’s presence relaxed him. She did not go to Belgium, of course, which was a mercy.

Gilles did seem a little uptight at Zolder, no question about it. “I don’t feel tense, no,” he said on the Friday, “but different. Until now the atmosphere in the team has always been easy, but after Imola it can’t be.”

One of the saddest aspects of Gilles’s death is that his last couple of weeks were so disillusioned. He had always wanted to win a race for Ferrari in Italy, where the tifosi loved him with a startling fervour.

At Imola he took the fight to Rene Arnoux, did all the work and was then duped by Didier Pironi on the final lap, when he thought they were cruising home. It would have been nice to record that he won his last race.

There is no doubt that, at Zolder, his main task of the weekend was to establish how things were going to be in the future. I was in the Ferrari pit when he left it for the last time. Tragedy very often amplifies hindsight, but I sensed the tension within him as he sat there, waiting for the right moment. Around him the photographers jostled, yet he sat there in the cockpit, perfectly still, eyes straight ahead. ‘GV very composed, waiting,’ says my notebook.

Usually, GV was very composed. “People say I am crazy because I get sideways sometimes. Jesus, let me tell you, a Ferrari driver who didn’t get sideways these last five years would not have been a racing driver! You know what, I remember Phil Hill saying that in 1961 he would very happily have swapped some of his horsepower for some of the British cars’ handling. Believe me, I know what he meant…”

That said it all. At no stage of his GP career did Gilles have a chassis remotely comparable with the best. Frequently he went into a race knowing he would have to stop for tyres, and yet he continued to charge, before the pitstop and after.

Villeneuve wrestling with his Ferrari became a familiar scene

Photo by: Ercole Colombo

“I think I can say quite honestly that I’ve never ever stroked in my racing career, and I’m proud of that. Even running 10th in a bad car you can have fun – but not if you’re stroking. Some guys I see out there… I wonder how they can accept their pay cheques!”

Gilles of course made a lot of money, but he lived simply. Yes, he made his home in Monte Carlo, after living for a while in a rented villa near Cannes, and he had a chalet in the mountains. That apart, the only extravagance of his life was his beloved Agusta helicopter.

“I never really wanted an ordinary aeroplane,” he would explain. “I’m basically lazy, and I like the convenience of a helicopter.”

His piloting had the Villeneuve touch. I remember Austria last year, for instance. After retiring from the race, he took off for Monaco, hovered above a couple of corners for a while, bowed to the paddock and left!

While Gilles was on the track, he was the focal point. You knew that, whatever the circumstances, he would be worth watching through a corner

“It’s the fastest of its class.” His eyes would light up as he spoke of the Agusta. And speed, in all forms, was essential to his life. At one stage, indeed, beating his 308 GTB record from Monaco to Fiorano was almost as important as setting a new track record when he got there…

At Watkins Glen one year we were driving down from the track to the village. At the exit of one corner was a wide expanse of grass – which was covered with skid marks. The word went around that they were the handiwork of a Fiat X1/9, on loan to G Villeneuve.

“Yes,” he grinned sheepishly, “I was trying to show Joanne that this was the car she should have.”

The fact was, he put his heart into everything. Think of the speedboat race at Lake Como last September (where he beat the six other GP drivers), or the dragster runs against the Italian Air Force Starfighter a couple of months later.

F1 wasn’t the only high-speed passion in Villeneuve’s life

Photo by: Sutton Images

Gilles warmed up the crowds by deliberately spinning the Ferrari at 130mph: “I never forget we have a responsibility to the fans.”

He used to say that often. “OK, sometimes I get pissed off if they want autographs when I’m trying to work, but I think motor racing treats the public very badly. I want to please them.”

That he did so is beyond question. While Gilles was on the track, he was the focal point. You knew that, whatever the circumstances, he would be worth watching through a corner. You understood why his hero had been Ronnie Peterson. You detected his spirit and commitment at all times, which is why it is such a task to select his most memorable races. I can never recall a day when he seemed to give less than everything.

PLUS: Villeneuve’s greatest F1 drives

Forget the glory days, like Long Beach 1979 or Jarama last year. Forget even the electrifying combat with Arnoux at Dijon, if you can. What of the countless unforgettable occasions when he stopped for a Ferrari-inevitable tyre change, then charged all over again, right to the end of the race, fifth or something behind people with a fraction of his talent.

One such drive in 1979 – Zolder again – brought him from 23rd to third. He drove so fast for so long that Ferrari fuel calculations were thrown out. Two hundred yards from the flag the T4 ground to a halt. Four points gone. With them, he would have been world champion that year.

Think of first qualifying at Watkins Glen that same year. Torrential rain – and Gilles was 11 seconds quicker than anyone else. Eleven! “That was fun,” he beamed afterwards.

And Monaco in 1980? The usual tyre stops in that one. In the late stages it was raining, and everyone was on slicks, most of them waving at the marshals to stop the race. Gilles ran at the limit, and beyond, lapping 5s faster than anyone else. Nothing will dim memories like that.

For me, Gilles was a consummate racing driver, with no weaknesses. Those who talked constantly of his impetuosity ignored the machinery with which he had to work. I will never believe, for instance, that anyone else would have won in that Ferrari in Spain last June.

Ah, Gilles, you stirred us so many times. I saw nearly all of your GP drives, and it was a privilege such as I do not anticipate again. At dinner that night at Zolder, we asked ourselves why, if it had to happen, did it have to happen to you, the most mercurial talent in the world?

And, of course, in the question lay the answer. A tempestuous ability such as yours left no margin. And it was for precisely that reason that we put you on a pedestal. We will miss you dearly.

PLUS: When Leclerc drove Villeneuve’s Ferrari

Villeneuve’s passing left a deep hole in the motorsport world

Photo by: Motorsport Images

In this article

Nigel Roebuck

Formula 1

Gilles Villeneuve

Ferrari

Be the first to know and subscribe for real-time news email updates on these topics

Subscribe to news alerts

Read the full article here