Jayson Stark was 16 years into what is now a 46-year Hall of Fame baseball-writing career when he walked into Baltimore’s Camden Yards on the night of Sept. 6, 1995, knowing exactly what was about to happen and having no idea what to expect.

Baseball’s most iconic moments are usually spontaneous in nature — the thunderbolt of Freddie Freeman’s walk-off grand slam in Game 1 of last October’s World Series or Kirk Gibson’s World Series Game 1-winning shot off Dennis Eckersley in 1988; Hank Aaron’s record-breaking 715th homer in 1974; the climax to Don Larsen’s World Series perfect game in 1956.

But Orioles shortstop Cal Ripken Jr. breaking New York Yankees legend Lou Gehrig’s consecutive-games streak to become baseball’s all-time Iron Man 30 years ago? Heck, you could see this one coming 2,131 miles away.

“Baseball history is normally unexpected — you don’t know when it’s going to be made, how it’s going to be made — and when it happens, that’s where the goose bumps come in,” said Stark, who writes for The Athletic and was a baseball columnist for the Philadelphia Inquirer in 1995.

“But in this game, everybody walked through the gates knowing exactly what was going to happen and when it was going to happen. The game was going to be halfway over, Ripken was going to have this record, and what more was there going to be? And boy, was I wrong. I’ve never been more wrong about any night I’ve spent at the ballpark.”

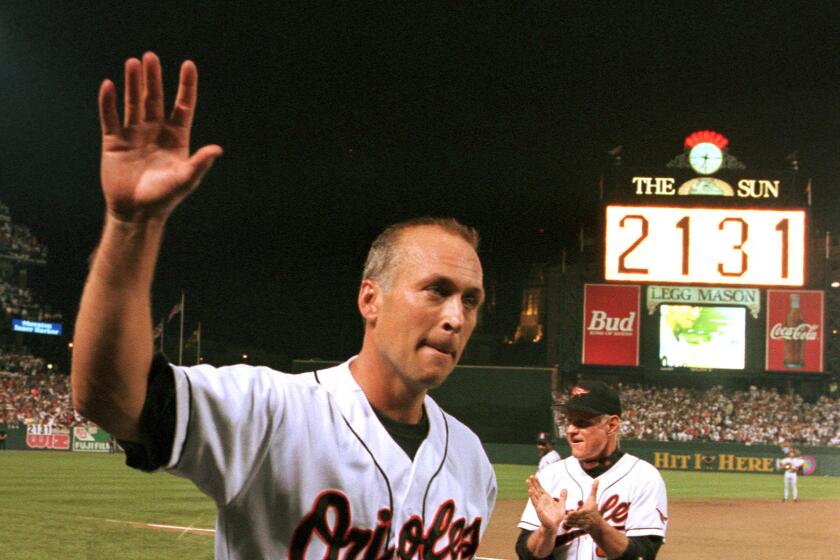

Cal Ripken Jr. acknowledges the fans as he gets a standing ovation for playing in his 2,131st consecutive game, breaking the record set by Yankees legend Lou Gehrig. (Focus On Sport / Getty Images)

Three decades after he broke Gehrig’s record by playing in his 2,131st consecutive game against the Angels, a streak that began in 1982, Ripken insists there was no plan for how he would celebrate when the game became official.

But neither he nor Major League Baseball could have written a better script for what transpired after Orioles second baseman Manny Alexander caught Damion Easley’s popup to end the top of the fifth inning, and blue-collar Baltimore witnessed the passing of the Iron Man torch to its lunch-pail-carrying son.

As a sellout crowd of 46,272 that included President Clinton, Vice President Al Gore and Hall of Famers Joe DiMaggio and Frank Robinson rose to its feet and the banners on the B&O Warehouse behind the right-field bleachers changed from 2,130 to 2,131, fireworks erupted and balloons and streamers soared into the air.

Ripken had jogged into the dugout but emerged for eight curtain calls, waving to the crowd and tapping his heart. He took off his jersey and gave it to his wife, Kelly, near the dugout. He hoisted his 2-year-old son, Ryan, into his arms and kissed his 5-year-old daughter, Rachel. He waved to his parents, Cal Sr. and Vi, in an upstairs luxury suite.

“It was really weird to have a stoppage in the middle of the game — it was like a rain delay,” Ripken said on a recent Hall of Fame podcast. “I kept getting called out for curtain calls, and Rafael Palmeiro said, ‘You’re gonna have to take a lap around this ballpark.’ Bobby Bonilla was standing right there and said, ‘Yeah, you gotta do that.’ ”

The teammates came out of the dugout and pushed Ripken down the first-base line, and off Ripken went on a victory lap around the stadium that delayed the game for 22 minutes and 15 seconds and helped pull baseball out of the doldrums caused by a nasty work stoppage that forced the cancellation of the 1994 World Series.

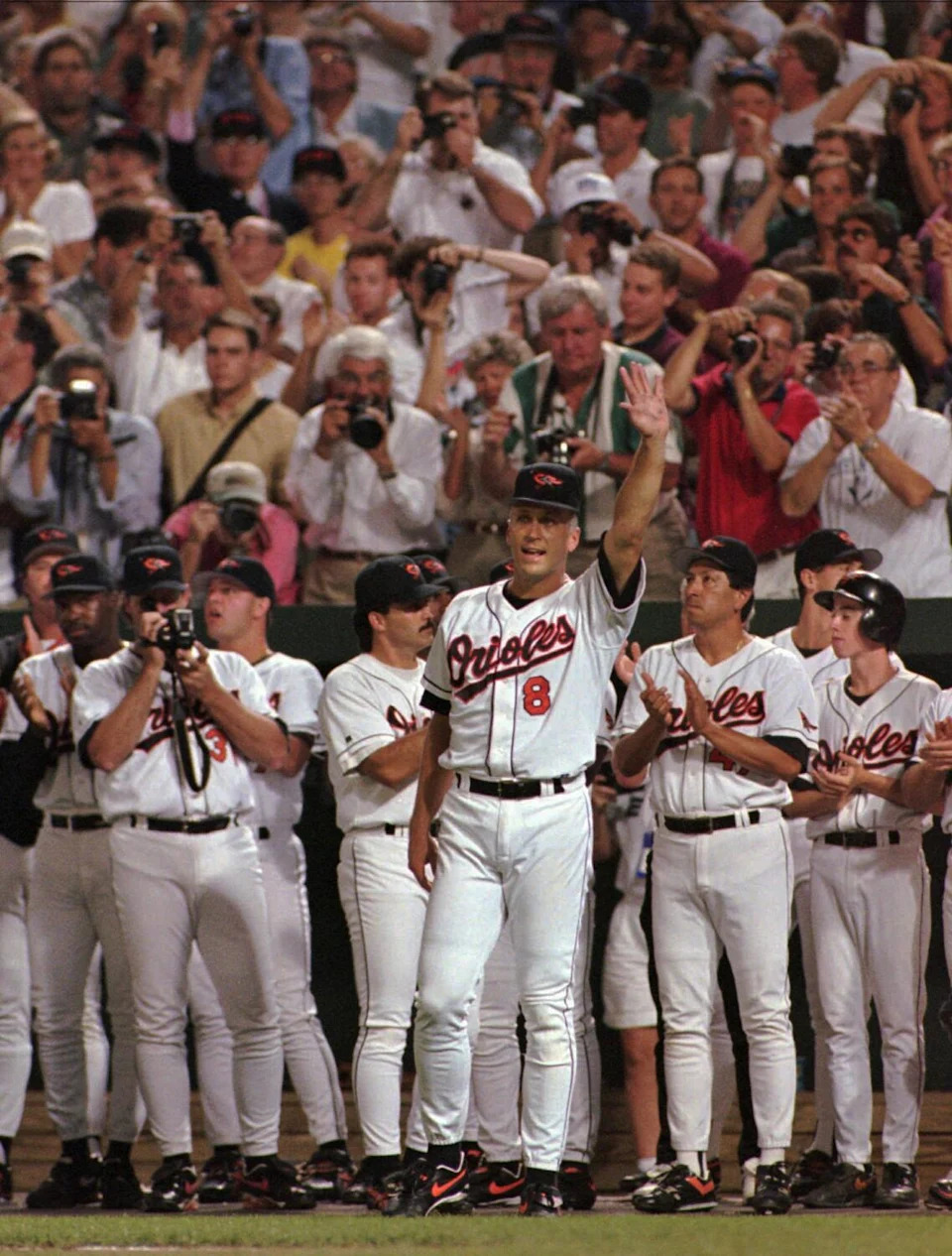

Cal Ripken Jr. waves to the crowd at Baltimore’s Camden Yards in the middle of the fifth inning of the Orioles’ game against the Angels on Sept. 6, 1995. (Denis Paquin / Associated Press)

Ripken started down the right-field line, shaking hands with fans in the front row. Around the outfield he went, greeting police officers and members of the grounds crew. Some fans tumbled out of the bleachers as Ripken leaped to high-five them. He exchanged hugs with the Orioles relievers.

“You start shaking hands and seeing people in the stands you had seen before — some you knew, some who you just knew their faces — and then it became more of a human experience,” said Ripken, who had homered in the fourth inning. “By the time I got around and past the bullpen, I [couldn’t] have cared less if the game started again.”

Around the left-field corner and down the left-field and third-base lines Ripken went, high-fiving fans, shaking the hands of everyone in the Angels’ dugout and embracing Angels hitting coach and Hall of Famer Rod Carew and slugger Chili Davis. Ripken even hugged the umpires.

The burst of a thousand flash bulbs lit up the stadium. Fans wiped away tears as they watched Ripken circle the field, and the thunderous applause never waned throughout the delay.

“The way the whole thing developed, it just felt organic and authentic, because it spoke to the power of numbers in baseball,” Stark said. “That was so much more than a number. It connected the moment to one six decades earlier. It connected Cal Ripken to freaking Lou Gehrig. It evokes memories and emotions unlike numbers in any sport.”

Even ESPN chose the pictures unfolding in Camden Yards over a thousand words, with ever-garrulous announcer Chris Berman turning off his microphone for 19 minutes before finally saying, “A moment that will live for 2,131 years … we will never see anything like this again.”

Ripken amassed 3,184 hits and 431 homers during his 21-year career. He won a World Series title in 1983, an American League rookie of the year award in 1982 and AL most valuable player awards in 1983 and 1991. He was a 19-time All-Star, two-time Gold Glove Award winner and was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2007.

Baltimore shortstop Cal Ripken Jr. stands with his Orioles teammates in front of the sign reading “2131” during postgame ceremonies celebrating Ripken’s surpassing of Lou Gehrig’s record of 2,130 consecutive games. (Denis Paquin / Associated Press)

But when he reflects on “The Streak,” which grew to 2,632 games before he pulled himself out of the lineup 10 minutes before the Orioles’ regular-season home finale against the Yankees on Sept. 20, 1998, he doesn’t elevate himself over any coal miner or schoolteacher who got up every morning and went to work.

“To me, the meaning of the streak is just showing up every day, being there for your team, trying to meet the challenges of the day,” Ripken said. “A lot of people thought I was obsessed with the streak and was obsessed with Lou Gehrig. I always laugh and say, I’d rather have more home runs than Hank Aaron and more hits than Pete Rose.

“But as an everyday player, there was a sense of responsibility instilled in me by my dad and the Orioles that your job is to come to the ballpark ready to play, and if that manager decides that you can help them win that day by putting you in the lineup, then you play.”

Read more: Jo Adell is a one-man wrecking crew as the Angels beat the Royals

The blue-collar work ethic that fueled The Streak and the class and style Ripken displayed that summer helped revitalize an industry that was still reeling from a devastating strike and long labor dispute that also forced the 1995 season to be reduced to 144 games, with a late April start.

“I think it was the single most important moment in the revival of baseball, the recovery of baseball, from that strike,” Stark said. “People just unloaded on our sport, and I just couldn’t get past the pain that whole season.

“And then Cal Ripken reminded everybody of what makes baseball special and what makes baseball different from every other sport on that night, with that record. The whole sport should be grateful to Cal for what he did.”

This story originally appeared in “Memories and Dreams,” the official magazine of the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. For more stories like this about legendary heroes of the game, subscribe to “Memories and Dreams” by joining the Museum’s membership program at www.baseballhall.org/join.

Get the best, most interesting and strangest stories of the day from the L.A. sports scene and beyond from our newsletter The Sports Report.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.

Read the full article here