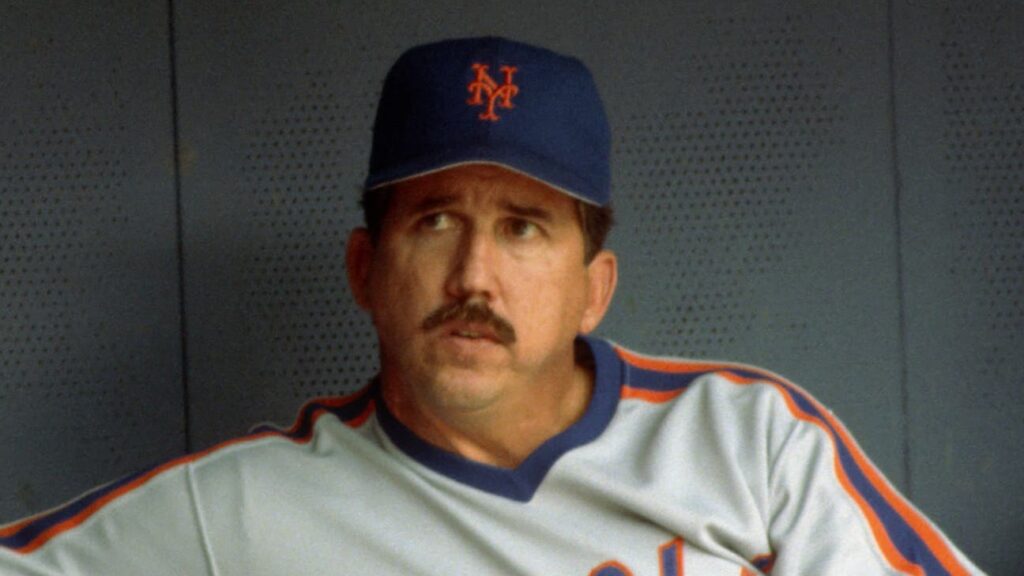

Born with a bravado to match that of the team he led to a world championship, Davey Johnson was the perfect manager for the 1986 Mets, brash enough to predict his ballclub would “dominate” the competition that season and immodest enough to howl “I told you so” when all was said and done.

Johnson, 82, died Friday night, leaving a legacy as an accomplished major league player and manager for several teams. He was most successful as a manager with the Mets, racking up 595 wins over six-plus seasons, the most by any skipper in team history.

Above all, he’ll always be remembered most fondly in New York for winning the second and still the most recent championship in the history of the franchise.

It took something of a miracle in Game 6 of that World Series against the Boston Red Sox to bring home the title, of course, with Mookie Wilson’s ground ball trickling through Bill Buckner’s legs to complete a two-out rally in the 10th inning. Yet in some ways, that too was fitting for the team and its manager, both forever oozing with a confidence that bordered on arrogance and created a belief that they couldn’t lose.

Johnson’s self-assurance was at the heart of what made Queens the place to be in the mid-to-late 1980s, the rare period in New York baseball history when the Mets, not the Yankees, unquestionably owned the city.

It was Davey, after all, who was secure enough in his ability that he managed with a loose rein, giving a famously boisterous group of players the freedom to flaunt their talent, speak their mind, and even publicly disagree with the manager on occasion.

In his 2018 book, “My Wild Ride in Baseball and Beyond,” Johnson succinctly summed up his style during his time with the Mets: “I just let everybody do their thing.”

Yet there was never any mistaking who was in charge, thanks to Johnson’s brilliant baseball mind. Even as a player who helped the Baltimore Orioles win championships in 1966 and 1970 — and lose to the upstart Mets in 1969 — Davey was always considered a deep thinker who was destined to manage.

In fact, as a young player, he was nicknamed “Dum-Dum” by some veteran Orioles who thought he was a little too smart for his own good at times.

“He was a guy who was always thinking about things,” Hall of Fame pitcher Jim Palmer once said about Johnson. “Very cerebral, even to the point of overanalyzing a situation, but I think that became one of his strengths as a manager.”

In fact, Johnson was ahead of the curve as one of the first managers to rely on a computer to give him an edge in creating lineups, bullpen matchups and the like. Analytics before there was such a thing, in a sense.

As a player, Johnson even tried to convince Hall of Fame manager Earl Weaver on the benefits of statistical analysis, as he recalled when he was hired to manage the Orioles for the 1996 season.

“I used to work on this program I called ‘optimizing the Orioles lineup,’” Johnson told reporters. “I would run it through the computer and bring the data to Earl Weaver. I found out that if I hit second instead of seventh, we’d score 50 or 60 more runs, and that would translate into a few more wins. I gave it to him, and it went right into the garbage can.”

Johnson was never shy about voicing his opinion on all matters baseball. It was a trait that would create conflict with Mets GM Frank Cashen and may well have hastened his departure when Cashen decided to fire him during the 1990 season.

It also led to some tension during his playing days with the equally headstrong Weaver, but eventually Johnson came to regard his Orioles’ manager as one of his mentors.

“He handled the pitching staff the right way,” Johnson once said of Weaver. “He knew how to use his relievers. He was a genius that way. I took it in.”

As a player, Johnson was a fixture at second base on those Orioles teams that went to the World Series four times from 1966 to 1971, winning three Gold Gloves and putting up solid offensive numbers.

It wasn’t until Johnson was traded after the 1972 season, reportedly because Weaver felt his second baseman was becoming more interested in bulking up to hit for power than playing defense, that he had his most memorable season.

Playing for the Atlanta Braves in 1973 at age 30, Johnson hit 43 home runs, setting a record for second basemen that stood until 2021 when Marcus Semien hit 45 with the Toronto Blue Jays.

Johnson never hit more than 18 in a season before or after that year, and by the mid-1970s, his stock had fallen to the point that he went to Japan to be a starter for two years before returning to the U.S. to finish out his career as a part-time player for the Philadelphia Phillies and Chicago Cubs.

After his playing days, Johnson got into managing due in part to his connection with Cashen, who had overseen baseball operations for the Orioles in the 1960s and 1970s before taking the GM job with the Mets.

Cashen hired Johnson in 1981 to manage in the minors with the Mets and then decided the time was right to promote him to manage the big-league club in 1984. With a wave of young talent led by Darryl Strawberry and Dwight Gooden, Johnson experienced immediate success, winning 90 games in ’84 and 98 games in ’85, both times falling short of the postseason at a time when there were no wild-card berths.

“Davey had great knowledge, and I think his real strength was knowing how to develop the young pitchers we had then,” former GM Joe McIlvaine, who was Cashen’s assistant in ’84, once said. “I don’t think anybody could have done a better job with Doc, with Ron Darling, and Sid Fernandez that first year. That set the trend for the next five years.”

After finishing behind the St. Louis Cardinals in the NL East in ’85, despite their 98 wins, Johnson wasn’t shy about predicting greatness going into the ’86 season. He told his team in spring training, and anyone who would listen, “We’re not just going to win, we’re going to dominate.”

His team backed up his words, winning 108 games and running away with the division title, then surviving an epic NLCS against the Houston Astros and finally coming back after losing the first two games of the World Series to defeat the Red Sox, miracle Game 6 comeback and all.

“Like I told you guys all along, there was never a doubt,” Johnson crowed gleefully after Game 7.

In total, for those five years that McIlvaine referenced, from ’84 through ’89, the Mets were the best team in the National League. However, their failure to win more than one championship left a sense that they didn’t fulfill their promise.

As such, Johnson eventually faced criticism from Cashen, who wanted his manager to be more of a disciplinarian. And then there was the 1988 NLCS, which the Mets lost in seven games to the Los Angeles Dodgers after having dominated them during the season, winning 10 of 11 games.

The turning point came in the ninth inning of Game 4 with the Mets poised to take a 3-1 lead in the series. Gooden, after walking light-hitting John Shelby, famously gave up a game-tying two-run home run to equally light-hitting catcher Mike Scioscia, and the Dodgers won the game in extra innings.

Though it was an era where pitchers routinely went much deeper into games than they do now, there was a case to be made that Gooden was running out of gas, especially after he walked Shelby. Yet over the years, Johnson remained defiant about his decision.

“That was Doc’s game,” Johnson said in 2013, when he was asked about it. “I’ve never had a second thought about leaving him in.”

True to his confident nature, Johnson rarely doubted himself, at least publicly, about any decision he made. But in 1990, with the Mets off to a 20-22 start, Cashen fired Johnson on May 29, replacing him with third-base coach Buddy Harrelson. The team went on to win 91 games but finished second in the division behind the Pittsburgh Pirates.

From there, Johnson went on to have success managing the Orioles, Cincinnati Reds, and the Washington Nationals, reaching the postseason with each of them, in addition to a stint with the Dodgers. A career managerial record of 1,372-1,071 (.562).

He won Manager of the Year awards in ’97 with the Orioles and then in 2012 with the Nationals in a distinguished career that, together with his playing accomplishments, has made his Hall of Fame candidacy on various veterans committees a subject of considerable debate.

Whether he ever gets into Cooperstown remains to be seen. However, Johnson is a member of the Mets Hall of Fame, with a legacy in New York that was forever secured with the ’86 championship that defined Johnson in so many ways.

Read the full article here